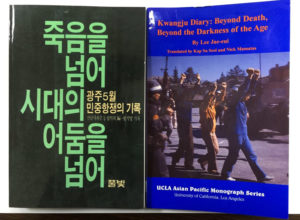

Lee Jae-eui’s Kwangju Diary, tells the first person account of Lee’s active involvement in the Gwangju Uprising as a sophomore at CNU. The text, which truly reads as a diary, recounts the days of the movement, including maps drawn by Lee[1] of the routes taken by both protestors and paratroopers. Its major strength lies in its clear and concise organization, utilizing time tables in order to create a chronological retelling of the events of the uprising. The footnotes within the text also add to the breadth of information within, including personal details of activists and reporters, offering a deeper understanding of the key players involved in the movement. But what is so important about this source, is its personal connection to the events of the uprising— it is a counter-site to the historia patria[2] that, for decades, has worked to discredit the movement. Where the Kwangju Diary falls flat is in its revision.

The original Kwangju Diary is nearly impossible to find— a target of heavy censorship, the diary’s production was not only limited but also strictly regulated[3]. The English revision, the only version I was able to obtain, has had entire chapters removed and replaced with essays written by Americans. Though these essays were written by Bruce Cummings, a historian as well as the world’s foremost expert on Korea, and Tim Shorrock, a writer and commentator on foreign policy and East Asian politics, and, while very informed on the subject matter, the omission of Lee Jae-eui’s own words is very upsetting. The choice of the translators and editors, also all American, to remove many of the names of locations and people in order to “clarify” the text for an English-speaking audience is also unacceptable. The text in its original form, is written from the bottom-up perspective— following Lee’s time as a student activist, Kwangju Diary offers an intimate look at the happenings of a city truly under duress. With the inclusion of Cummings and Shorrock’s essays, we are also given a top-down, outside perspective of the uprising. Since both of their editions were written well after the actual event, they offer a more nuanced, scholarly, rather than emotional, view of the massacre.

It is quite clear that in the English revision, that the intended audience is that of an uninformed, English-speaker. The book includes a detailed account of the translation process as well as a note from Lee where he discusses the creation of the English version. Again, we see what weakness the text has when analyzing who was involved in the editorial process[4] because of the lack of the involvement of Korean scholars.

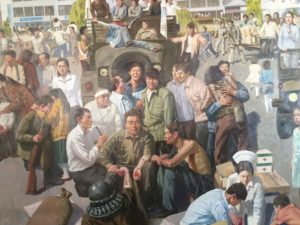

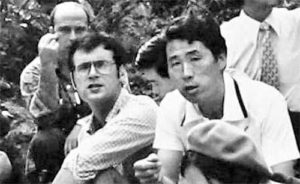

Where Lee Jae-eui’s Kwangju Diary offers a written account of the Gwangju Uprising, 5.18 힌츠페터 스토리, a documentary utilizing the smuggled footage of German reporter, Jürgen Hinzpeter showcases how heinous the attacks on the citizens of Gwangju truly were. Originally aired over the course of 15 years as a Sunday special, the film, 5.18 힌츠페터 스토리[5], brings together the decades old footage of Hinzpeter from the uprising juxtaposed to interviews conducted from 2003-2018.Compiled, directed, edited, and narrated by KBS producer, Jane Youngjoo, the film works to create a cohesive story of Hinzpeter and the footage that made him famous.

Unlike Lee’s diary, Hinzpeter’s footage within the film is not censored. Bloody, beaten bodies, both alive and dead, in caskets and left on the streets, are filmed. The abuse of power and blatant lies told by Korean officials, that the protestors were “communist insurgents” is exposed. The original footage and photographs within the documentary were not commissioned; Hinzpeter had frequently visited Korea in the past working as a correspondent in Japan for the ARD[6]. Within the documentary, Hinzpeter tells how, after being alerted of the situation in Gwangju by German missionary, Paul Schneiss, he headed to Gwangju. Though I am uncertain if the documentary was commissioned or not, it was produced under KBS[7]. Responsible for everything from the news, to variety and music programs, to dramas, KBS maintains its status as a long-standing and dominant force within the Korean media sphere. To ignore the influence and power that KBS has as a broadcasting company would be ignorant. Though this documentary may have been produced solely for educational purposes, one simply cannot ignore the inherent biases held by such a powerful organization.

Other than the inclusion of interviews of survivors of the Gwangju Uprising, The Hinzpeter Story showcases footage of the uprising as it occurred— the atrocities committed by the paratroopers that the government adamantly denied[8] and worked to censor, were put on display for the world to see, and the news footage of this discovery is included. Like Lee’s diary, these images act as counter-sites to the historia patria. However, with the inclusion of recent scholarship, the documentary also sheds light on the United State’s involvement[9] in the uprising in new and profound ways.

While the film works hard to bring attention the the uprising, it has a tendency to over embellish details of key players such as Kim Sa-bok[10], changing their narratives entirely. Rather than recognized for his role in Hinzpeter’s ability to collect the footage of Gwangju, he is reduced to simply the “taxi driver” that meets Hinzpeter by happenstance. Though this is rectified later in the film as his son, Kim Seung-pil, gives his own interview, Kim Sa-bok’s story lacked the attention that Hinzpeter’s had, and as a result, there is no interview done by Sa-bok, as he died prior to the film’s completion[11].

In conjunction, these sources serve as a testimony to the violence Gwangju faced at the hands of its own government. Though these sources work well on their own, it is through the analysis of both of them together that a deeper understanding of just how bad the treatment of civilians were during this time. Without those that sacrificed themselves for this democratization movement, Korea would be much different from what we know it as today. It is also safe to say, that without the production of these sources that the world may never have known the sacrifices of Gwangju. Sources on the events in Gwangju remain very difficult to find and out of what is made available to the public, the perspectives offered in both Lee’s Kwangju Diary and Hinzpeter’s found footage within 5.18 히츠페터 스토리 are some of the most personal accounts on an event that would go down in history as a testament to the tenacity of those fighting an authoritative regime, and paving the way for South Korea’s future democratization.

[1] The images of the maps within the English revision were all redrawn by Seiee Kim of the Pratt Institute, and do not include the original location names in order to make it more “accessible” to an English-speaking audience.

[2] Putnam, Lara. “The Transnational and the Text-Searchable: Digitized Sources and the Shadows They Cast.” The American Historical Review 121, no. 2 (2016): 377–402. https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/121.2.377. Pg. 381

[3] The revised English version was also very difficult to find. If not for the dark web, I may not have been able to find this source OR 5.18 힌츠펱 스토리. Sources to come from Korea during this time remain heavily censored, with access still restricted.

[4] Outside of Lee Jae-eui, only three Koreans were involved in the reproduction of this text. Mentioned above, Seiee Kim was responsible for the reproduction of the maps, Kap Su-seol, the translation, and Soo Kyung-nam for proof-reading. As such, this text is presented, not as a translation, but as a “revised edition” (Lee, 9).

[5] Translated as The Story of Hinzpeter

[6] ARD, short for Arbeitsgemeinschaft der öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, is an independent broadcasting station founded in West Germany, 1950, that focused on post-war broadcasts.

[7] KBS, short for Korean Broadcasting System, was founded by the government in 1927, with it becoming independently owned in 1973, stands as one of the largest and most profitable broadcasting companies in Korea.

[8] Deniers of the Gwangju Uprising remain in Korea, and it is commonly used as a test to see who is and is not a right-wing conservative versus a left-wing progressive.

[9] The Cherokee Files is a collection of declassified documents that contradict previous statements made by the United States government on their role and involvement in the Gwangju Uprising. Included in the files, is a document stating that not only did President Carter’s administration know about President Chun’s intended use of military force in Gwangju, but they supported it, knowing of the plan a full ten days prior to the deployment of troops to Gwangju.

[10] The film Taxi Driver is the greatly loved, though inaccurate, retelling of Kim Sa-bok’s involvement with Hinzpeter.

[11] His son, Kim Seung-pil, would say in another interview, that the liver cancer his father died from in 2016 was largely caused by his father’s heavy drinking after witnessing the uprising, telling his son that he deplored how how “members of the same people can be so cruel to each other”.